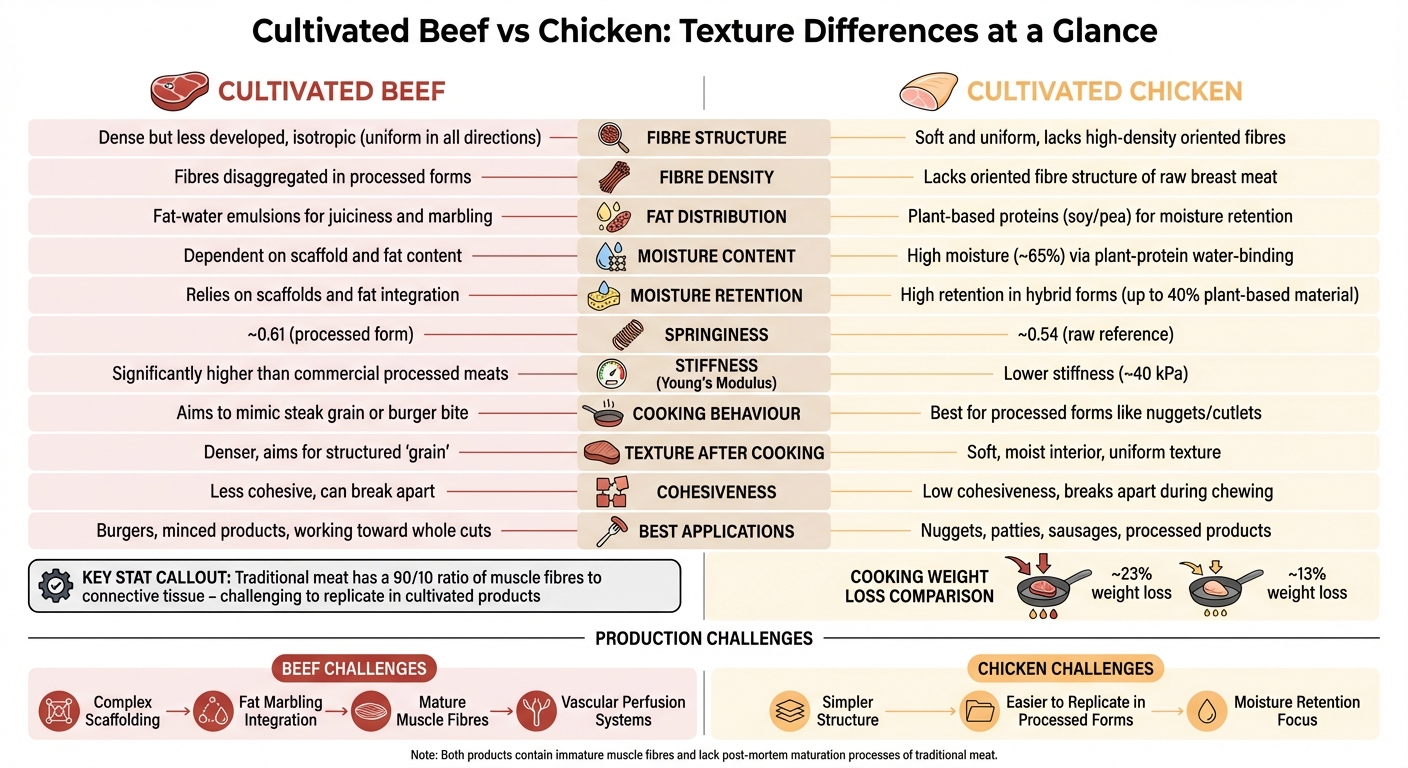

When it comes to cultivated meat, texture is a major factor in how it feels, cooks, and tastes. Cultivated beef and chicken both aim to replicate the qualities of their conventional counterparts, but they differ in several ways:

- Beef: Known for its dense, fibrous structure and marbling, cultivated beef struggles to replicate the mature muscle fibres and fat distribution of conventional beef. Producers use scaffolds and fat–water emulsions to mimic these qualities, but the texture can feel less cohesive, especially in whole cuts like steaks.

- Chicken: Softer and less fibrous, cultivated chicken is easier to replicate for processed products like nuggets or patties. However, it lacks the structural complexity of conventional chicken breast, making it less suitable for whole cuts.

Both products face challenges like immature muscle fibres, limited fat integration, and moisture retention. While cultivated chicken generally feels softer and more uniform, cultivated beef tends to be denser but less developed in its fibre structure. This highlights the ongoing work in solving consistency issues in cultivated meat to match traditional textures. These differences mean each type of meat has specific strengths and limitations in the kitchen.

Quick Comparison

| Aspect | Cultivated Beef | Cultivated Chicken |

|---|---|---|

| Fibre Structure | Dense but less developed | Soft and uniform |

| Fat Distribution | Fat–water emulsions for juiciness | Plant-based proteins for moisture |

| Moisture Retention | Relies on scaffolds and fat content | High due to plant-based materials |

| Cooking Behaviour | Aims to mimic steak or burger grain | Best for processed forms like nuggets |

Understanding these differences can help you decide which product works best for your preferences and cooking needs.

Cultivated Beef vs Chicken Texture Comparison Chart

I Tried Cultured Meat: Is It The Future of Food?

sbb-itb-c323ed3

How Cultivated Beef Feels and Behaves

Cultivated beef has a unique dual nature, behaving like a viscoelastic material, which influences how it feels when pressed, cut, or chewed [3]. This sensation is shaped by two key factors: the muscle fibres themselves and the way they are held together.

Unlike conventional beef, the muscle fibres in cultivated beef are immature, containing neonatal or embryonic forms of actin and myosin rather than the fully developed proteins found in traditional meat [4]. These thinner, less developed fibres contribute to a different mouthfeel.

Mechanical tests reveal some interesting contrasts. Cultivated beef products, such as sausages, tend to exhibit higher stiffness (measured as Young's Modulus) compared to commercial processed meats [2]. However, they often lack cohesiveness, which affects their texture [2].

Traditional beef owes much of its texture to its complex composition - approximately 90% muscle fibres, 10% connective tissue, along with fat and vascular tissues [2]. Cultivated beef, at least in its current form, lacks this intricate structure. Additionally, it skips the "rigor mortis" stage, a natural process in conventional meat where a pH drop activates enzymes that tenderise the tissue [4]. Without this process, cultivated beef producers must find alternative methods to replicate the desired tenderness.

Fat Distribution in Cultivated Beef

Fat distribution plays a crucial role in creating juicy, flavourful meat. In conventional beef, marbling - those streaks of fat interspersed with muscle - is a hallmark of quality. To mimic this in cultivated beef, producers need to grow muscle cells (myoblasts) alongside fat cells (adipocytes) within the same culture [4].

This process is far from straightforward. Muscle and fat cells require different nutrient environments to thrive, making it difficult to find a medium that supports both [4]. Early prototypes of cultivated beef were found to be drier, largely due to insufficient fat [4].

For minced products like burgers, fat can be added during later stages of production. However, for whole cuts such as steaks, the fat must be integrated into the 3D structure as it develops [4]. Achieving this requires advanced scaffolding systems or perfusion networks to deliver nutrients and oxygen throughout the thick layers of cells. The release of fat during chewing is what gives the sensation of "fattiness" in the mouth, making its distribution essential for an authentic eating experience [5].

Technical Difficulties in Creating Beef Texture

Replicating the intricate 3D architecture of beef is one of the biggest challenges in producing cultivated meat. Mercedes Vila, CTO at BioTech Foods, highlights this complexity:

Understanding cultivated meat final characteristics such as texture is necessary for optimising the production and scalability phase [6].

Traditional beef has a highly organised structure, with muscle fibres aligned in specific directions and surrounded by layers of connective tissue (endo-, peri-, and epimysium), interwoven with fat and blood vessels [2]. To recreate this, producers use edible scaffolds made from materials like collagen, fibrin, or alginate [4].

These scaffolds not only guide cells to grow in the correct orientation but also help them differentiate into the appropriate tissue types. However, without a vascular-like perfusion system to distribute nutrients deep into the tissue, producers are currently limited to growing only thin layers of cells [4]. This limitation makes producing thick, whole-cut steaks particularly challenging.

To enhance the diameter and structure of muscle fibres, some producers are experimenting with electrical or mechanical stimulation during the cultivation process [4]. These stimuli mimic the natural stresses muscles experience in living animals, encouraging cells to develop more mature, robust structures. Additionally, the choice of scaffold material can influence the final texture. For instance, collagen scaffolds might yield a different texture than plant-based fibres, and they can also affect the nutritional profile by altering the amino acid composition or adding dietary fibre [4]. These technical details are critical in meeting consumer expectations for an authentic beef-like texture.

How Cultivated Chicken Feels and Behaves

Cultivated chicken has a softer and more uniform texture compared to its traditional counterpart. This difference stems from the absence of the intricate bundle structure found in conventional poultry. For instance, traditional chicken breast is made up of roughly 90% muscle fibres and 10% connective tissue[2]. Replicating this complexity remains a challenge for cultivated meat producers. As a result, cultivated chicken feels less fibrous, and its softness impacts how it behaves when subjected to deformation.

When it comes to mechanical properties, cultivated chicken reacts differently. Tests reveal it has higher springiness (0.61) than fresh chicken (0.54)[2]. This means it is more responsive to the speed of deformation but recovers more slowly after being compressed. Traditional chicken, on the other hand, is more fibrous and uneven, showing greater resilience but also experiencing permanent deformation after chewing[2].

One of the main hurdles for cultivated chicken is moisture retention. Unlike traditional chicken, which benefits from natural post-mortem processes to lock in moisture, cultivated chicken requires alternative strategies. Producers often turn to specific protein sources, such as algal proteins, to enhance water retention and deliver a juicier, softer texture[3].

Softness and Moisture in Cultivated Chicken

The tender texture of cultivated chicken comes from its immature muscle fibres and the lack of organised connective tissue present in traditional poultry. Without tendons, blood vessels, or the directional fibre orientation typical of whole-muscle cuts, cultivated chicken naturally feels softer and more delicate[3].

To address moisture retention, producers carefully select protein sources and processing techniques, often using hydrocolloids to maintain structure and reduce water loss[3]. However, finding the right balance is tricky - too much moisture can make the texture overly soft, while insufficient moisture leads to dryness.

Another challenge lies in the cohesiveness of cultivated chicken. Its low cohesiveness means it tends to break apart during chewing, making it difficult to replicate the structural integrity consumers expect from products like chicken breast. These textural challenges make cultivated chicken more suitable for processed formats rather than whole-muscle cuts.

Best Uses for Cultivated Chicken Products

The softer and more uniform texture of cultivated chicken lends itself well to processed products like nuggets, patties, and sausages. These items don’t rely on complex structural organisation, making them easier to produce[3]. High-moisture processing techniques can further refine properties such as springiness and cutting strength, helping these products come closer to the mouthfeel of traditional processed chicken.

While cultivated chicken performs well in these applications, its uniform texture presents both opportunities and challenges in the kitchen. Unlike fibrous meats like beef, cultivated chicken can replicate the initial "first bite" hardness but struggles to maintain fibre integrity as it is chewed[2][3].

Cultivated Beef vs Chicken: Texture Comparison

When comparing cultivated beef and chicken, their textural differences are immediately noticeable. Traditional meat typically has a 90/10 fibre-to-connective tissue ratio[2], which is challenging to replicate in cultivated products like sausages or mince. These processed versions lack the organised structure of traditional meat. Cultivated beef is generally isotropic, meaning its texture is uniform in all directions. In contrast, traditional meat has an anisotropic structure, where texture varies depending on the muscle fibre direction[7]. This makes cultivated chicken softer and less fibrous, while cultivated beef often has a denser protein matrix.

Fat distribution is another key factor in texture and mouthfeel. Studies show a strong correlation (ρ = 0.9762) between "fattiness" and perceived "meat-like" quality[7]. To recreate the juicy, fatty texture of traditional beef, cultivated beef uses fat–water emulsions. On the other hand, cultivated chicken relies on plant-based proteins like soy or pea protein to retain moisture[5]. This difference gives cultivated beef a richer, more indulgent feel, while cultivated chicken is lighter and more delicate, with a distinctive poultry taste.

Moisture retention also sets the two apart. Traditional chicken loses around 23% of its weight during cooking, compared to just 13% in many cultivated alternatives[5]. Cultivated chicken, often a hybrid product with up to 40% plant-based material, retains moisture effectively thanks to the water-binding properties of plant proteins[8]. In contrast, cultivated beef relies on its scaffold structure and fat content to maintain juiciness[1].

"Cultured meat is still mainly obtained from a muscle tissue production by cells, and its organoleptic development after the cell culture is under study."

– Nature[2]

Texture after cooking further highlights their differences. Cultivated beef aims to replicate the "grain" of steak or the bite of a burger. Meanwhile, cultivated chicken behaves more like processed products - think nuggets or cutlets - with a soft, moist interior[8]. Cultivated beef is stiffer, with a higher Young's Modulus and springiness (~0.61) compared to raw chicken (~0.54)[2], while cultivated chicken maintains a consistently soft texture.

Comparison Table

| Texture Attribute | Cultivated Beef | Cultivated Chicken |

|---|---|---|

| Fibre Density | Isotropic; fibres disaggregated in processed forms[2] | Lacks high-density oriented fibres of raw breast meat[2] |

| Fat Distribution | Fat–water emulsions for juiciness[5] | High moisture (~65%) via soy or pea protein binding[5] |

| Moisture Retention | Dependent on scaffold and fat content[1] | High retention in hybrid forms due to plant-protein water-binding[8] |

| Consistency After Cooking | Aims to mimic the "grain" of steak or burger bite[1] | Behaves like processed chicken (nuggets/cutlets) with a soft, moist interior[8] |

| Springiness | ~0.61 (processed form)[2] | ~0.54 (raw reference)[2] |

| Stiffness (Young's Modulus) | Significantly higher than commercial processed meats[2] | Lower stiffness (~40 kPa for poultry references)[7] |

These contrasts highlight the challenges and opportunities for brands as they refine the textures of cultivated meats.

How Different Brands Approach Texture

To replicate the texture of traditional meat, producers rely on three key strategies: scaffolds, co-culturing cell types, and binding ingredients.

Scaffolds provide a 3D framework for cells to grow and develop. In October 2019, Harvard researchers, led by Kit Parker and Luke MacQueen, successfully grew cow and rabbit muscle cells on edible gelatin scaffolds. They used nanofibres to mimic the grain of beef. Luke MacQueen explained the importance of this approach:

To grow muscle tissues that resembled meat, we needed to find a 'scaffold' material that was edible and allowed muscle cells to attach and grow in 3D [1].

Other producers have experimented with hydrogels made from materials like collagen or alginate and micro-carrier beads derived from cellulose or chitosan. These materials support large-scale, moist cell growth [9].

Beyond scaffolds, brands refine texture by co-culturing different cell types. Traditional meat is a mix of about 90% muscle fibres and 10% connective tissue [2]. By mimicking this complexity, co-culturing enhances the texture of cultured meat. For instance, in January 2023, BioTech Foods in Spain revealed their research on combining muscle and fat cells to create Frankfurt-style sausages. These sausages achieved mechanical properties comparable to commercial meat. Mercedes Vila, the company's co-founder and CTO, emphasised:

Research into texturization is one of the decisive steps in defining the production and scalability phase of cultured meat in which we find ourselves [10].

For beef, co-culturing can replicate the marbling that affects hardness and chewiness. For chicken, it improves the juiciness and softness that pure muscle cultures often lack [9].

Binding agents also play a crucial role, helping to aggregate cells into familiar meat-like shapes. In April 2023, researchers at Tufts University's Center for Cellular Agriculture, led by John Yuen Jr. and David Kaplan, developed bulk porcine fat tissue using alginate (a seaweed-derived binder) and microbial transglutaminase. Alginate provided fat with pressure resistance similar to natural livestock fat, while microbial transglutaminase produced a texture closer to rendered lard or tallow [12]. David Kaplan highlighted the significance of this method:

This method of aggregating cultured fat cells with binding agents can be translated to large-scale production of cultured fat tissue in bioreactors - a key obstacle in the development of cultured meat [12].

Producers also incorporate plant-based proteins, such as soy and pea, into hybrid products. These proteins create a dense, fibrous base that works well for both beef and chicken alternatives [11].

In practice, producers often combine these techniques. For instance, they might use gelatin scaffolds alongside co-cultured muscle and fat cells, bound together with alginate. This flexibility allows them to replicate the marbled texture of beef or the soft, moist feel of chicken, addressing the specific textural challenges of cultured meat.

Summary

Cultivated beef and chicken differ in texture due to their unique cellular structures. Traditional meat typically has a 90/10 ratio of muscle fibres to connective tissue[2], which is challenging to replicate. Beef, for instance, requires detailed scaffolding and cultivated fat marbling to achieve its firm, structured texture. In contrast, chicken’s simpler and softer texture lends itself more easily to replication, especially in processed forms.

Mechanical tests reveal that sausage-style cultivated meats come close to matching the hardness of commercial meat[2]. However, these products often feel firmer yet less cohesive, meaning they can break apart more easily when chewed. Interestingly, cultivated meat demonstrates a springiness (0.54) close to that of raw chicken (0.61)[2].

These textural differences stem from the absence of post-mortem maturation and the complexity of multiple tissue types. To address these challenges, producers use techniques like scaffolds, co-culturing, and binding agents. These methods help refine textures, whether replicating beef’s marbled density or chicken’s distinctive softness.

For those curious about these advancements, Cultivated Meat Shop offers helpful guides to navigate these innovations. As cultivated meat becomes more accessible in the UK, understanding these textural nuances will empower shoppers to choose products that best fit their cooking preferences.

FAQs

Why doesn’t cultivated beef feel like a real steak?

Cultivated beef tends to have a softer and less fibrous texture when compared to traditional steak. This difference arises because it doesn’t yet replicate the intricate structure and elasticity found in conventional whole cuts like steaks. Although progress is being made, matching the texture of traditional meat continues to be a major focus for cultivated beef producers.

Why is cultivated chicken better in nuggets than whole breast?

Cultivated chicken tends to perform better in nugget form than as a whole breast. Why? It can be shaped into smaller, uniform pieces that closely mimic the texture of traditional chicken nuggets. Thanks to developments in tissue engineering - such as hollow fibre perfusion - these nugget-sized pieces achieve a consistent texture while retaining the taste and sensory experience of conventional chicken.

Will cultivated beef and chicken cook differently at home?

Yes, cultivated beef and chicken might behave a bit differently in the kitchen. Their softer, less fibrous texture and lack of connective tissue can change how they react to cooking methods like boiling or searing. You may need to tweak your techniques slightly to get the results you're after.